Ancestors with Disabilities

-

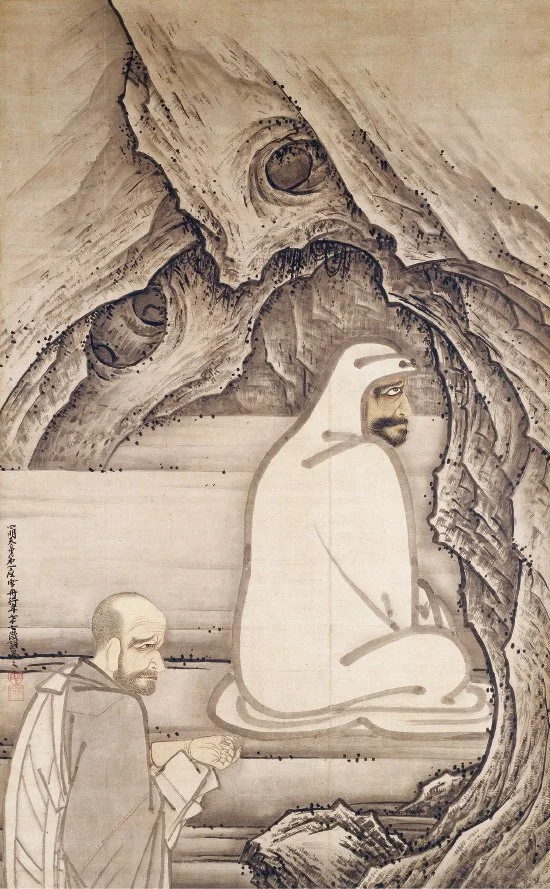

2nd Zen Ancestor Dazu Huike (大祖慧可 487–593)

Dazu Huike, the Second Patriarch of Chinese Zen (Chan), is a pivotal figure in the lineage, known for receiving the mind-to-mind transmission from Bodhidharma. His dedication was so profound that he famously cut off his own arm to demonstrate his sincerity, a radical act often interpreted as a metaphor for transcending the body and ego. Huike’s story, though extreme, can also be seen through the lens of disability: he continued to practice and teach despite his self-inflicted amputation, offering a powerful, if stark, example of resilience and non-attachment to physical form. In this light, Huike’s legacy affirms that awakening is not limited by bodily ability, challenging ableist assumptions in spiritual communities. His life reminds us that the Dharma is accessible and alive in all bodies, regardless of form or function. -

3rd Zen Ancestor Jianzhi Sengcan (鑑智僧璨 529-613)

Sengcan (鑑智僧璨), the Third Patriarch of Chan (Zen) Buddhism in China, holds a vital place in the Zen lineage for his role in transmitting the Dharma from Dazu Huike to Daoxin and for authoring the Xinxin Ming (Faith in Mind), one of the earliest and most profound Zen texts. Though historical details are scarce, some traditions suggest Sengcan lived with chronic illness or leprosy, which lends deeper meaning to his emphasis on equanimity and non-dual awareness beyond bodily conditions. His teachings, particularly in the Xinxin Ming, emphasize radical acceptance and stillness—foundations that have deeply shaped both Chinese and Japanese Zen. Sengcan’s example broadens the understanding of who can be a spiritual exemplar, pointing to a Zen that embraces both vulnerability and awakening. -

Jianzhen (鑒真 688-763)

Jianzhen (Ganjin in Japanese), a blind Chinese monk of the Tang dynasty, played a pivotal role in transmitting Buddhist monastic discipline and precepts to Japan in the 8th century. Despite losing his eyesight after multiple failed sea voyages, his unwavering determination led him to successfully bring the Vinaya and Chinese Buddhist practices to Japan, where he profoundly shaped the formation of Japanese Buddhism, including Zen. His disability did not hinder his mission—it became a testament to the power of resilience and spiritual vision beyond physical sight. Jianzhen’s legacy invites a deeper recognition of disability not as limitation, but as part of the richness of the human condition within the Buddhist path. He is honored at Tōshōdai-ji in Nara, where his teachings and example continue to inspire. -

Hisako Nakamura (中村久子 1897–1968)

Jodo Shinshu Writings…

Her book “Hands and Feet of the Heart”

More info coming soon -

Ōishi Junkyō (大石順教 1888–1968)

Ōishi Junkyō’s life stands as a powerful testament to resilience and the transformative potential of embodied practice in Japanese Buddhism. Having lost both arms in a violent attack during her years as a geisha, she taught herself to write and paint with her mouth, mastering calligraphy and poetry that deeply influenced the aesthetic and spiritual culture of the Edo period. In founding Bukkōin Temple in Kyoto, Junkyō not only created a haven for monastic training but also modeled genuine inclusivity, demonstrating that disability is not a barrier to profound spiritual insight or leadership. Her legacy continues to inspire communities to honor diverse abilities and to make the Dharma accessible to all. -

The "Unnamed Leper"

The Unnamed Leper (from the Kūṭṭhi Sutta, Ud 5.3)

– An account in the canonical Kūṭṭhi Sutta describing a practitioner suffering from leprosy whose physical affliction became a catalyst for deep insight into impermanence and suffering. His story is used as an example of how even extreme physical hardship can lead to profound spiritual realization…

More info coming soon -

"Suppabuddha the Leper"

Suppabuddha the Leper (Suppabuddha-kuṭṭhi; c. 5th–4th century BCE): Udāna 5.3 (Kuṭṭhi/“Leper” Sutta); Dhammapada v.66

More info coming soon

-

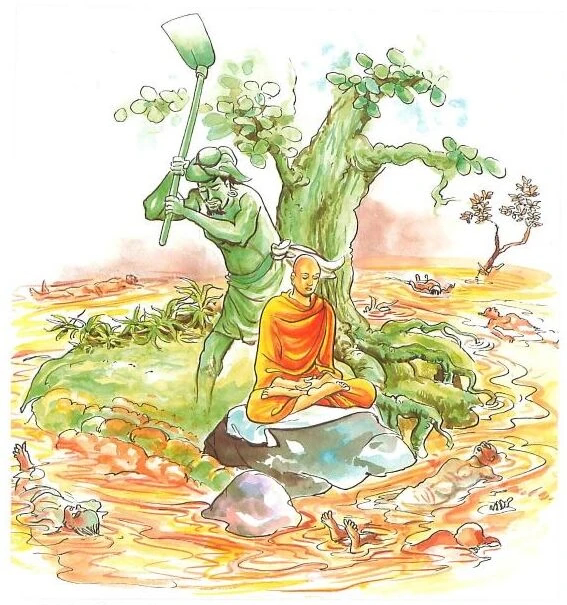

Cūḷapanthaka

(Culapanthaka, Cūḷa Panthaka); Udāna 5.10 (Panthaka Sutta); Apadāna (Cūḷapanthaka thera-apadāna, Tha-Ap 16).

Chulapanthaka was the younger brother of the monk Mahāpanthaka. He struggled to memorize even a single verse and was mocked by some as slow or unfit for monastic life. When he was left out of a meal offering Chulapanthaka had prepared to leave the Order, but the Buddha stopped him and gave him a simple, embodied practice: to sit, and to clean, and to repeat “rajoharaṇam” (“taking on/removing impurity”), and to keep his attention on that activity. Seeing his cloth become soiled, Chulapanthaka realized how greed, hatred, and ignorance “soil” the mind. It was this insight, won through patient and tactile practice, that helped lead him to his awakening. (Dhp-aṭṭhakathā: Cūlapanthaka-vatthu)

This story reframes disability and learning difference: what looked like a cognitive limitation became the ground of a power teaching: embodied attention, steady repetition, and dignity in practice. The Buddha later entrusted Chulapanthaka to teach; and despite early doubts, he taught with great clarity and spiritual depth. (Dhp-aṭṭhakathā; cf. Dhp v.25)

Holding up Chulapanthaka as model the Buddha said…“Through diligence, mindfulness, discipline, and control of the senses,

let the wise one make of himself an island which no flood can overwhelm.”

— The Buddha (Dhp v.25) -

Khujjuttarà "the Hunchback"

Khujjuttarà (Paramatthadīpanī, Apadāna, and Theragāthā 205–206)

More info coming soon

-

Bhaddiya the "Little Elder"

Bhaddiya (aka “Lakuntaka Bhaddiya” or the “little elder”, described in Udāna 7.5 and SN 21.6 and Theragāthā 491–496 )