Phoenix Cloud Lineage

Shakyamuni Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha, or “the Awakened One”, was a historical teacher who lived in South Asia around the 6th or 5th century BCE. Born into a royal family of the Shakya clan in what is now Nepal, he left his privileged life after encountering the realities of aging, illness, and death. Seeking a path beyond suffering, he pursed years of ascetic practice before realizing that liberation lay not in extremes, but in a Middle Way. Sitting in meditation under the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, he awakened to the nature of reality and the causes of suffering.

For the rest of his life, the Buddha taught a path of ethical living, meditative practice, and insight, summarized in the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. He emphasized that freedom comes through direct experience and personal realization. The Buddha passed into parinirvana in Kushinagar, leaving behind a living tradition that has taken many forms across time and culture, always pointing toward the possibility of awakening within this very life.

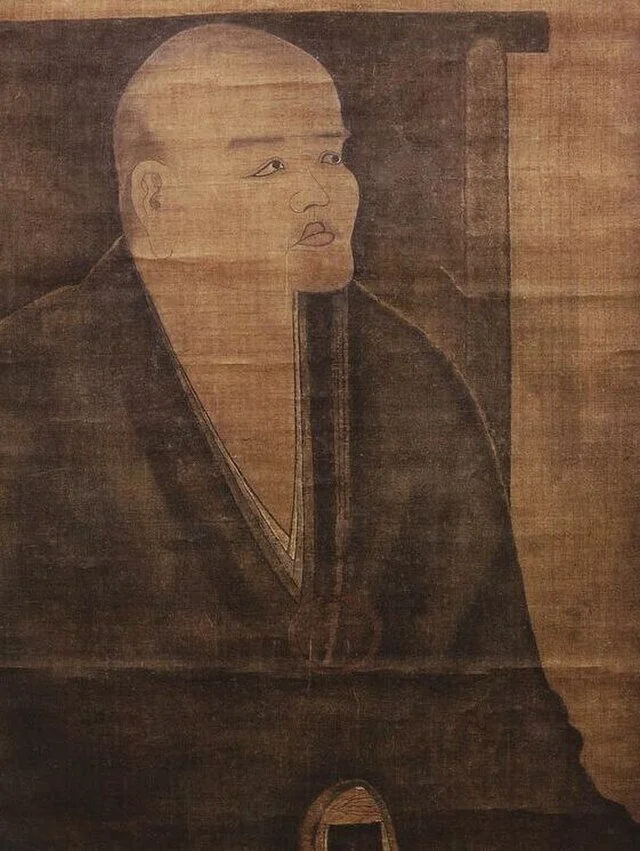

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE and is traditionally recognized as the first ancestor of Zen in China. While little reliable biographical information survives, early Chinese sources describe him as coming from the Western Regions, possibly South India or Central Asia, and later legend calls him the 28th Patriarch in a line tracing back to the Buddha. Though his life became layered with myth, Bodhidharma remains a vivid presence in Zen lore, often depicted as a foreign, wild-eyed ascetic known as “the Blue-Eyed Barbarian.”

He is credited with introducing an approach to practice based on meditation and insight into the nature of mind, teaching that awakening arises through observing the mind directly. According to legend, he met Emperor Wu of Liang but rejected the emperor’s conventional ideas about religious merit. He later spent nine years in seated meditation at Shaolin Monastery, a symbol of steadfast practice. His transmission of the Dharma to his student, Huike, is considered the beginning of the Zen lineage in China, a tradition grounded clarity over concepts, and realization over beliefs.

Dōgen Zenji

Dōgen (1200-1253) was a Japanese Buddhist teacher, philosopher, and poet whose legacy has shaped the Soto Zen tradition and continues to influence spiritual seekers worldwide. Ordained as a Tendai monk in early adolescence, Dōgen became dissatisfied with prevailing doctrines and traveled to China in search of a more authentic expression of the Buddha’s teachings. There, he encountered the teacher Rujing and experience a profound spiritual teaching, which he later described as “casting off body and mind.”

Returning to Japan, Dōgen devouted his life to articulating and transmitting a path centered on wholehearted sitting meditation, or zazen. He founded Eiheji monastery in the mountains of northern Japan, where he lived, taught, and worked extensively. His major works, including Fukanzazengi, Bendōwa, and the Shōbōgenzō, emphasize direct experience, disciplined practice, and the interpretation of everyday activity and awakening. Rather than rely on hierarchy or ritual display, Dōgen taught that realization is always present in the very act of sincere practice.

Kōdō Sawaki

Kōdō Sawaki Roshi (1880-1965) was a pivotal figure in 20th-century Zen Buddhism, known for revitalizing the Sōtō school and making Zen practice accessible outside of traditional monastic structures. Orphaned at a young age and raised in harsh conditions, Sawaki’s life was marked by resilience, directness, and an unwavering commitment to the practice of zazen. Often called “Homeless Kōdō” because he refused to settle at any one temple, Sawaki Roshi travel widely throughout Japan, emphasizing that seated meditation, or zazen, was not a method to attain enlightenment but the expression of enlightenment itself.

Sawaki Roshi was a sharp critic of modern society’s obsession with status, conformity, and material success, speaking out against what he called “group stupidity” and the commodification of education and human life. His teachings continue to resonate for their directness and clarity. Among his many students was Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi, who would go on to teach widely in the United States and Europe, carrying forward Sawaki’s emphasis on grounded, wholehearted practice.

Kōbun Chino Otogawa

Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi (1938-2002) was a Japanese Sōtō Zen priest who played a formative role in bringing Zen to the United States and Europe. A student of Kōdō Sawaki Roshi and a graduate of Kyoto University with a master’s in Mahayana Buddhist studies, he trained at Eiheiji, one of the most prestigious Sōtō Zen monasteries in Japan. In 1967, at the invitation of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Kobun came to the U.S. to assist in establishing practice at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. He soon became the resident teacher at Haiku Zendo in Los Altos California, and went on to found both the Phoenix Cloud lineage and Jikoji Zen Center in Los Gatos, California. He also taught at centers across California, New Mexico, Colorado, and throughout Europe.

Kobun was widely respected for his humility, poetic style, and deep sincerity. He preferred to avoid formal titles, encouraging students to discover truth through their own direct experience rather than deference to hierarchy. His Zen emphasized subtle presence, spaciousness, and “just sitting” — a soft, open awareness free from striving. Kobun transmitted the Dharma to several students but considered transmission to be an intimate and informal process, not just a ceremonial formality. Deeply influential yet understated in demeanor, he shaped generations of American Zen students through his quiet example and unconventional approach.

In 2002, Kobun died tragically in Switzerland while trying to rescue his young daughter, Maya, who also drowned. His death was widely mourned across multiple Buddhist communities. He is remembered not only for his teachings but also his gentleness, his resistance to institutionalization, and the quiet depth of his presence, whether in ceremony, calligraphy, or the simple gesture of adjusting a student’s posture with the gentlest hands.

Shōhō Mike Newhall

More info coming soon

Ōshin Jennings

More info coming soon